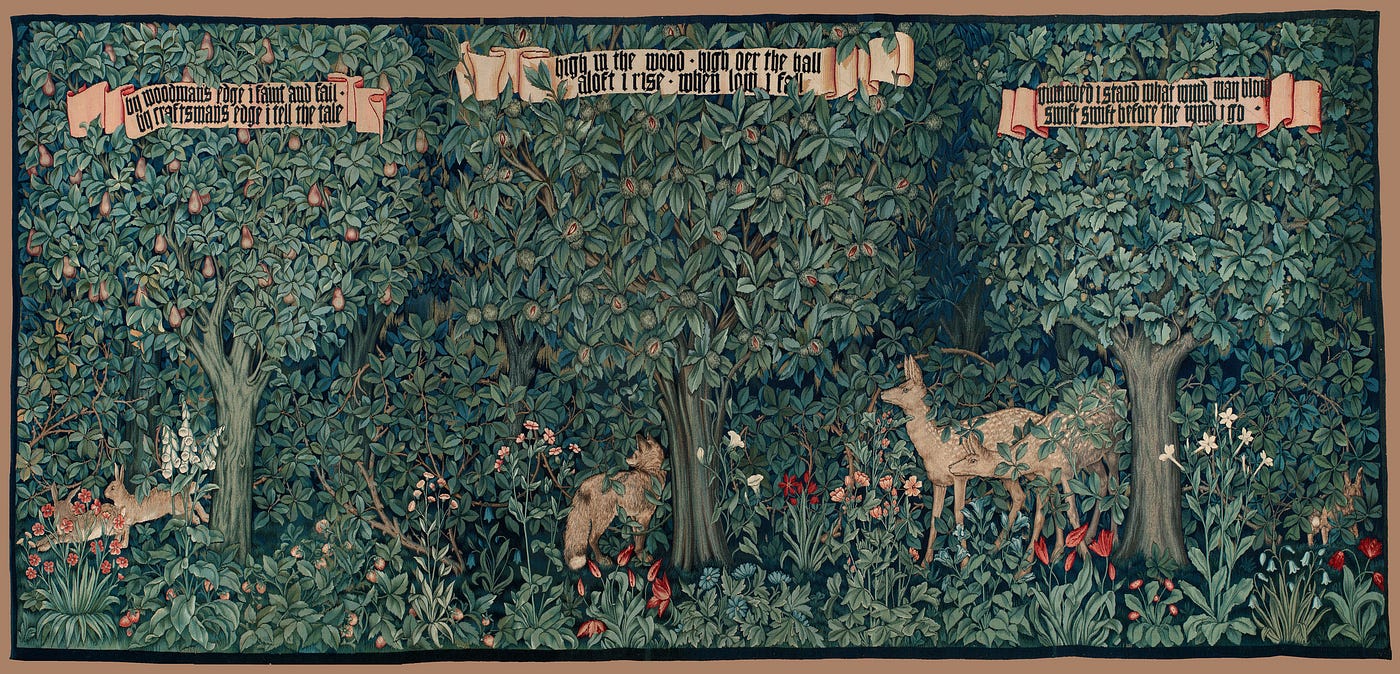

Even before the age of mass consumption, designers sought (more or less successfully) to promote worthy values and positive behaviours through their work. William Morris (1834 to 1896); is perhaps the most well known exponent of this approach and reacted against the evils of industrialisation. Morris shunned modern production methods in favour of more labour intensive artisanal ones that he thought were better than working in the new fangled factories of the Victorian age. He was probably right.

A complex character was William. An entrepreneur who lived with all the trappings of the Victorian well to do, who could at the same time manipulate the boardroom like the most dastardly Dickensian. He was incredibly earnest in mastering medieval craft techniques, popularising nordic verse and doing right by the workers, he employed. Perhaps, most surprising of all, was his accolade as ‘the best-known British Marxist of his century’ (CPGB, 2009) and his patronage of of early workers newspapers. This practical embodiment of nineteenth century sentimental individualism is underplayed in the design literature, which naturally privileges his creative work.

Whitely (1999, p221) summarises the utopian mission of Morris and his ilk, as shifting from ‘the virtue of the maker, through the integrity and aesthetics of the object, to the role of the designer — and consumer — in a just society.’ Integrity is a mutable term. Within modernity it became as much about the doing of design as the outcome as consumable goods and capital in general. In this sense, the ethical strand in design evolved from crafting nice wallpaper in Arts and Craft studios, toward tackling the potential benefits and harm of ‘use’ of a product or service in the domain of consumption.

Modernists had some great ideas about improving the lot of the masses, but often failed in the important delivery bit. It was all slightly dehumanising. Le Corbusier’s (1887 to 1965) notions of ‘machines for living’ quite quickly descended from sunny chic ateliers in Provence to the sink estates of brutalist seventies Britain. Grim came later, and at the start the idealists gamble to turn every dream house out of pre-fabricated moulds held the potential to bring cool to the masses. What they (Gropius’ Bauhaus) did do was to put design practice at the centre of design education, through making stuff, designers learn, experiment and become better practitioners.

“Bauhaus workshops are laboratories in which prototypes of products suitable for mass production are carefully developed and continually improved,”

Walter Gropius.

That sounds like Lean. An important milestone in ethical design was ergonomics. Rather than utopia, Henry Dreyfus (1904 to 1972) wanted to make the world around us nice, more comfy and slightly cool through a Californian kind of Hyyge. For the post-war optimists, his classic works span archetypal trains to telephones that embody the American century and mark the rise of professionalisation of Product, Graphic and most importantly, Industrial Design. His design principles are a conduit for concern for the individual (Cited in Woodham,1997, p124), even if the user is not aware of this duty of care, through high quality ergonomics. Humanistic empathy, methodical professionalism and growing market demand built on technologically advanced product lines, together helped conceive his famous work on anthropomorphic guidelines for products:

Like the great American Design movie stars (e.g. Loewy) he was also a savvy self-publicist and entrepreneur to boot, helping to shift design out of artworking and into consulting and broader strategic business activities. As with most ethical solutions, ergonomics has its dark side, with a heritage founded in optimising mechanical weapons and human performance to the boundaries of endurance. Probably no ones knows if ergonomics has saved or lost more lives.

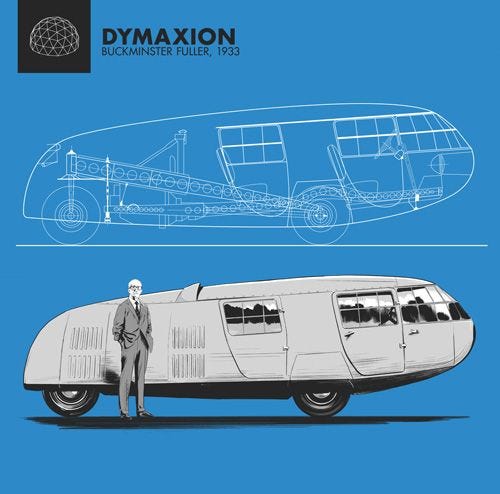

Of course, the second world war did much to stem the utopian tradition. But the slow but steady economic boom that followed, accelerated technical innovation, especially in the areas of aerospace, computing, transportation and latterly space flight. Buckminster Fuller reflected the post-war tech confidence, proposing futuristic inventions that married sci-fi creativity hi-jinks with bean counting frugality through his ‘doing more with less’ philosophy for resource utilisation:

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the old model obsolete.”

Buckminster Fuller

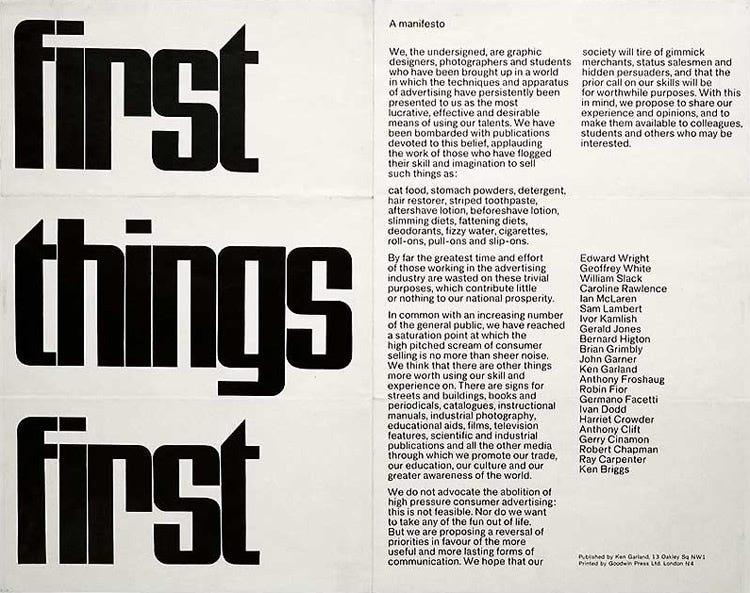

You don’t see so many Dymaxions in the roads these days. Fuller’s frugality was a natural precursor to Victor Papanek (1923 to 1998). He was instrumental in joining ecology (Carson, 1962) to design in the post-modern world just as Motown was hitting slowdown. Interestingly, unlike all of the other designers discussed so far, his oeuvre focused almost entirely on ideas, books, lectures and teaching than commercially available and viable products. As the white heat of technology cooled, waves of unrest turned into a global movement for change, spookily anticipated by the First Things First manifesto:

‘Written in 1963 and published in 1964 by Ken Garland along with 20 other designers, photographers and students, the manifesto was a reaction to the staunch society of 1960s Britain and called for a return to a humanist aspect of design. It lashed out against the fast-paced and often trivial productions of mainstream advertising, calling them trivial and time-consuming. It’s solution was to focus efforts of design on education and public service tasks that promoted the betterment of society.’ (Design History)

The trend to dematerialisation continues with the vogue for ‘Design Thinking’ as output of creative endeavours. Even more recently, ‘Design for Society’ by Nigel Whitely (1997) surveys creative endeavours in sustainability, as well as efforts in promoting gender equality and a diversity of issues. Indeed, Charter and Tischner (2001) describe the range of contemporary ethical concerns designers have and are tackling right now, including countering globalisation right through to the more prosaic level (Abbot and Tyler, 1997) of crime prevention.

Just when utopianism seemed dead it was resurrected. Morris’ worker activism, combined with Dreyfuss’ designerly duty of care and the Bauhaus’ immersive design as learning approach melded with British socio-technical research (e.g. Tavistock Institute) and Nordic social democratic politics into the participatory design movement (Ehn, 1988). The UTOPIA project (Ehn, ibid), took a moral perspective on the introduction (and design) of computing technology into print workers practice and operationalised this stance through a pragmatic design process that shifted designers’ role from originators to facilitators.

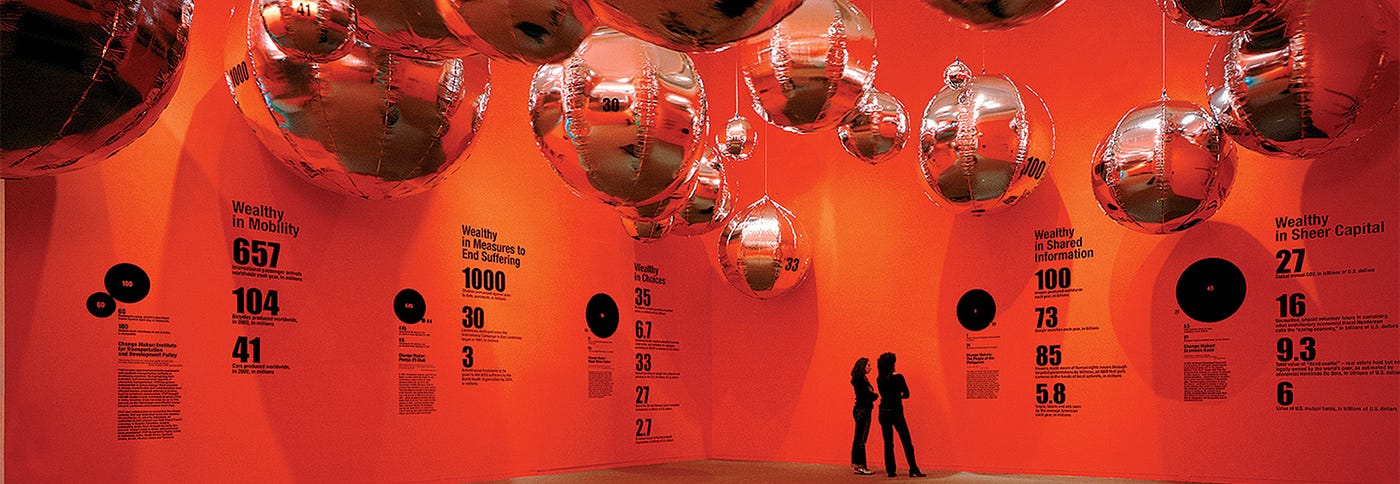

In many ways, all that ethical stuff shaped today’s UX and Service Design disciplines. These approaches, with their intrinsic values, aim to do good, even if at worst it’s about removing barriers to conversion in the stuff people desire for. Instrumental value has evolved too. Nowadays we’re no longer wowed by functions and features but expect such ethically charged qualities as ‘desirable’ and ‘engaging’ experiences. In this context, and in the ever more complex nexus of stuff and people interactions: ethical design just got more complicated, to do, predict and measure. Bruce Mau’s book, exhibition and various media outputs, captures this energy in finding ‘hundreds of examples where visionaries were using design to effect positive change in the world. We called this pattern “Massive Change”.’

Here’s a very long word. Postphenomenology. I’m not entirely sure what phenomenology is when its at home, let alone any pre or post conditions it may have but Kristina Höök recommended I should read the work of Sabrina Hauser and I did and its a critical inflection on design ethics. Wallpaper aside, this article has made little mention of the outcome of design, whether that be a product, service or experience. A postphenomenology perspective might suggest that these outcomes are not passive things that come out of the end of a sticky-note session, but are in fact critical to our ethical understanding and agency. For example, the use of an IoT device might drive us to consider lots of things, we might not be able to fathom as non-users and/or in isolation from such devices.

Whatever the case, the context of ‘smart’, ‘connected’, ‘artificial’ thingness is an important final topic to tackle. What do all of these new fangled technologies do? Are they inherently neutral, or good or evil? How do we make use of them in our product and service designs? There is perhaps an implicit assumption these technologies are particularly morally tricky. That may be true or not, perhaps they are just the latest incarnation of zeitgeist fears like horseless carriages, the mob, daytime TV or many other moral panics.

The historical perspective is important here. Yes, society faces ambiguous futures where unbridled technological advances outstrip human values and social structures. But let that possibility not detract from the manifest troubles of our time. Hunger, injustice, inequality and the gamut of basic human rights that need defending and progressing, as Morris’ early socialists fought for suffrage and wages. Stuff over that, however scary is secondary to building a just economy enabled by digital cooperation.

Here we are then, at the end. The point of ethical design is not just to understand the world but to change it. In the modest but amazingly creative ways designers do stuff. Let’s not aggrandise that potential. Just as Morris’ vision of a gilded future never materialised (things got a lot, lot, lot worse) and many of Buckminster Fuller and Victor Pananek’s design’s never left the drawing board, our ability to change the world around us is conditional on what we can realistically do.

Even understanding the impact of new technologies is hard. And as designers we should recognise we may not be best equipped to make that call. What we should do is extend our participatory philosophy to ethics; we need to work with a broad range of people to understand (and design) good stuff out of the new challenges/opportunities we face. Finally, in this story and you will almost certainly noticed the injustices of the past:women rather than men are leading that change today.

Despite the worthy ideals of the ethical design tradition, critics position it as at best a naïve reaction of bystanders, looking on at dangers that can never be solved by designers, nor potentially even rightly understood by them fully. In many ways, the notion of ethical practice overstates the capability of the discipline. Tinkering with the form of things is perhaps at best a diversion from political life from this perspective and at minimum obscures who, how and why decisions are made in manufacture that have negative repercussions.

Of course it’s easy to baulk at the fluff and folksy flow of worthy design that arguably tends to perpetuate Morris’ tradition rooted in archaic craft production and opposition to technology (e.g Woodham, 2004) and consumption. Tote bag or Thermidor? In some cases this strand in design focuses on symptoms that are amenable to the discipline (e.g. packaging) rather than the underlying causes: over consumption (Chapman, 2005, p24). But let’s not get negative nor forget that power of the moral perogative in the arts that have led to, amongst other things, Guernica and Pop!

The ethical design tradition embraces pragmatism (how design can help solve problems) as well as utopianism (how can we envision a better future). In some ways, you could even say that design is applied ethics as every product, service and experience has a future life that impacts individuals and society at some level. Of course, there is a risk that this future orientation shifts focus away from the important jobs to be done in the here and now. We see this in contemporary movements in what we might call Design Futurism, where critical, speculative noodling produces great ideas but go nowhere, to paraphrase Morris.

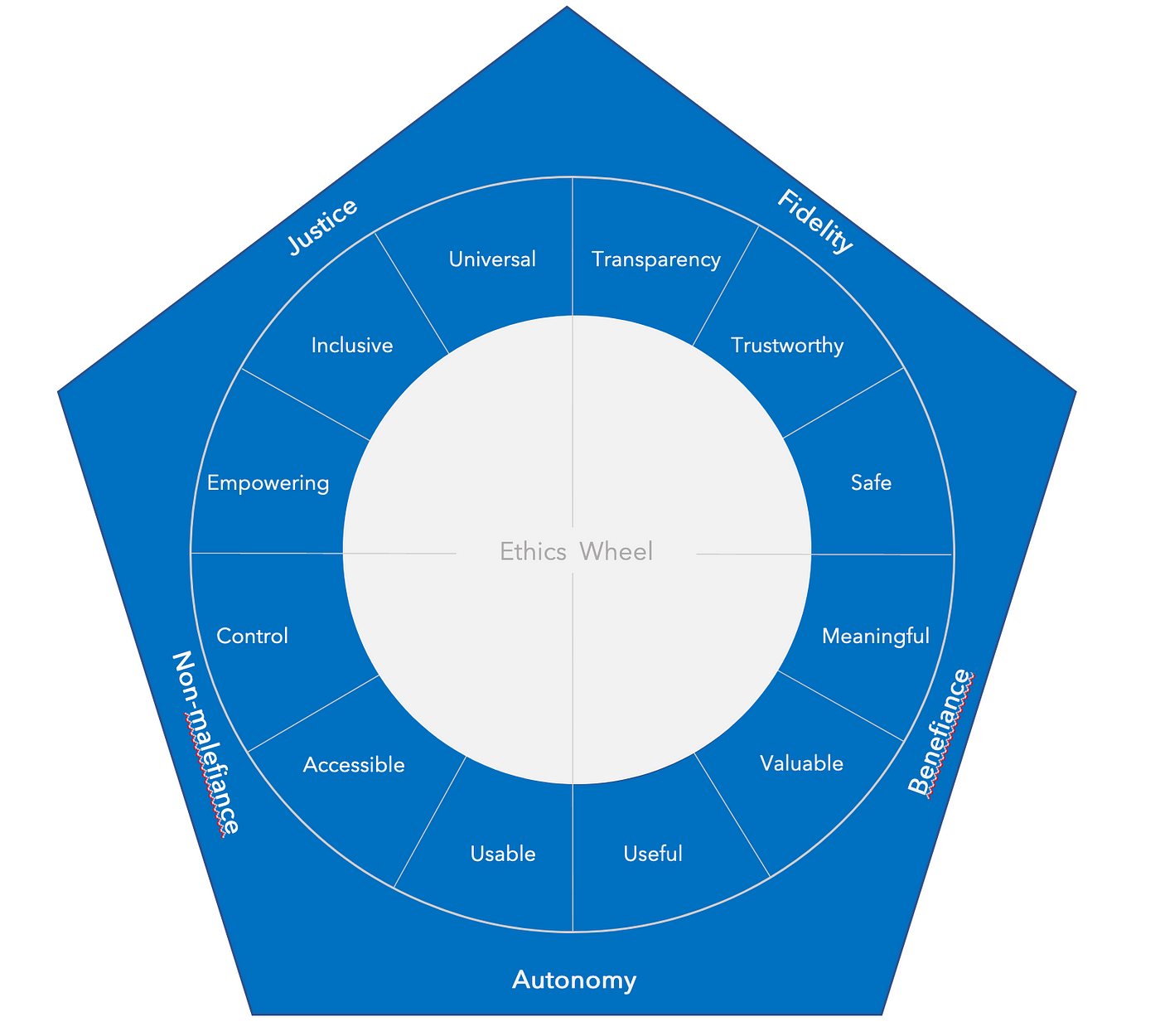

Instead of chiding creatives for wanting to do good let’s agree that designers’ are in a good place, in their heads and within society, to try to influence things for good. Maybe if its only by a nudge. They think, create, imagine and help shape stuff, so they should help progress the right stuff and defer on the bad. Most importantly they are doing that with rather than for people now. In advocating human-centred tools, methods and processes that are mature, effective and help people come together to solve things and do things for the better. Not only does creative work make people happier it helps us all to be in a strong position to influence how stuff gets made for the better. In this sense, what is most good about ethical design is not always its products, but always in its underlying and applied humanistic philosophy to do good work. A practical way to achieve this is through using the ethics wheel:

© John Knight, 2004 to 2021

REFERENCES

Abbott, H and Tyler M. (1997). Safer by Design, A Guide to the Management and Law of Designing for Product Safety. Gower Publishing, (The Design Council), Aldershot, England. ISBN; 0566077078

Carson, R. (1962). Silent Spring, Boston, Houghton Miflin.

Chapman, J. (2005). Emotionally Durable Design, Objects, Experiences and Empathy. Earthscan Publications Ltd, London. ISBN, 1844071812

Charter, M and Tischner, U. (2001) Sustainable Solutions, Developing Products and Services for the Future. Greenleaf Publishing. ISBN 1–874719–36–5

Ehn, P. (1988): Work-Oriented Design of Computer Artifacts,

Almquist & Wiksell International Publ., Stockholm. Chapter 13: Case II: The UTOPIA Project

Fevre. R. (2017). Individualism and Inequality: The Future of Work and Politics

Knight, J (2004). Design For Life: Ethics, Empathy And Experience. In: A. Dearden and Watts, L (Eds.). Proceedings of Design for Life: British HCI Group Conference, 2004. Vol 2. Leeds, 6th to 10th September 2004.

Papanek, V. (1981). Design for the Real World, Human Ecology and Social Change.Thames and Hudson, London. 102.

Whiteley,N. (1997).Design for Society. Reaktion Books. ISBN, 0948462655

Woodham, J. M. (2004). Twentieth Century Design. Oxford University Press. 019–284204–8

Leave a Reply